Well, that's the question we asked anyway.

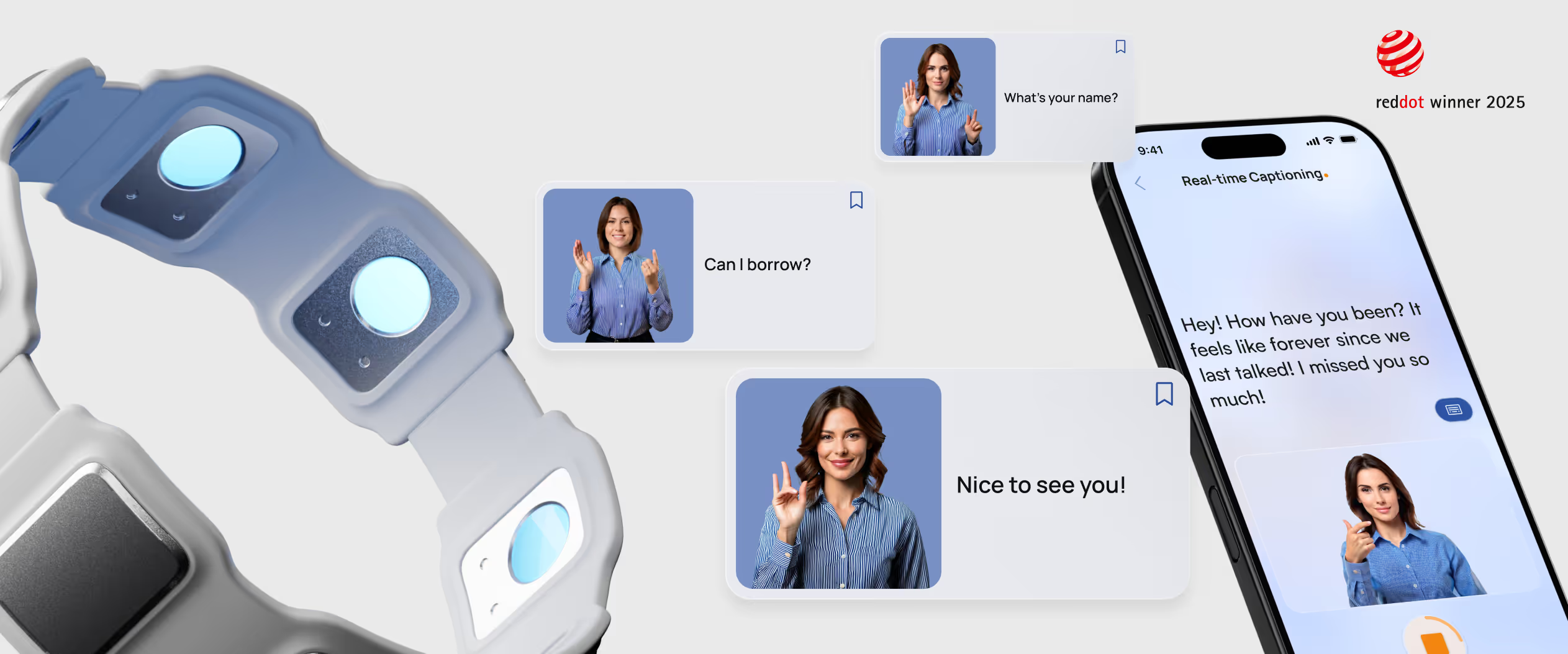

As an answer, we developed DARI

Not intended to replace interpreters, DARI instead looks to empower those in the Deaf community to be their own interpreters in those casual and immediate contexts when accessing an interpreter is either unavailable or inconvenient.

Red Dot, 2025: Brands and Comm. design

my role: Research Lead & UX Engineer

- organized the project’s data collection and formative testings through SME interviews, focus groups and participatory research activities

- lead my team through a Reflexive Thematic analysis of our data which enabled a deep understanding of the problem space and its opportunities.

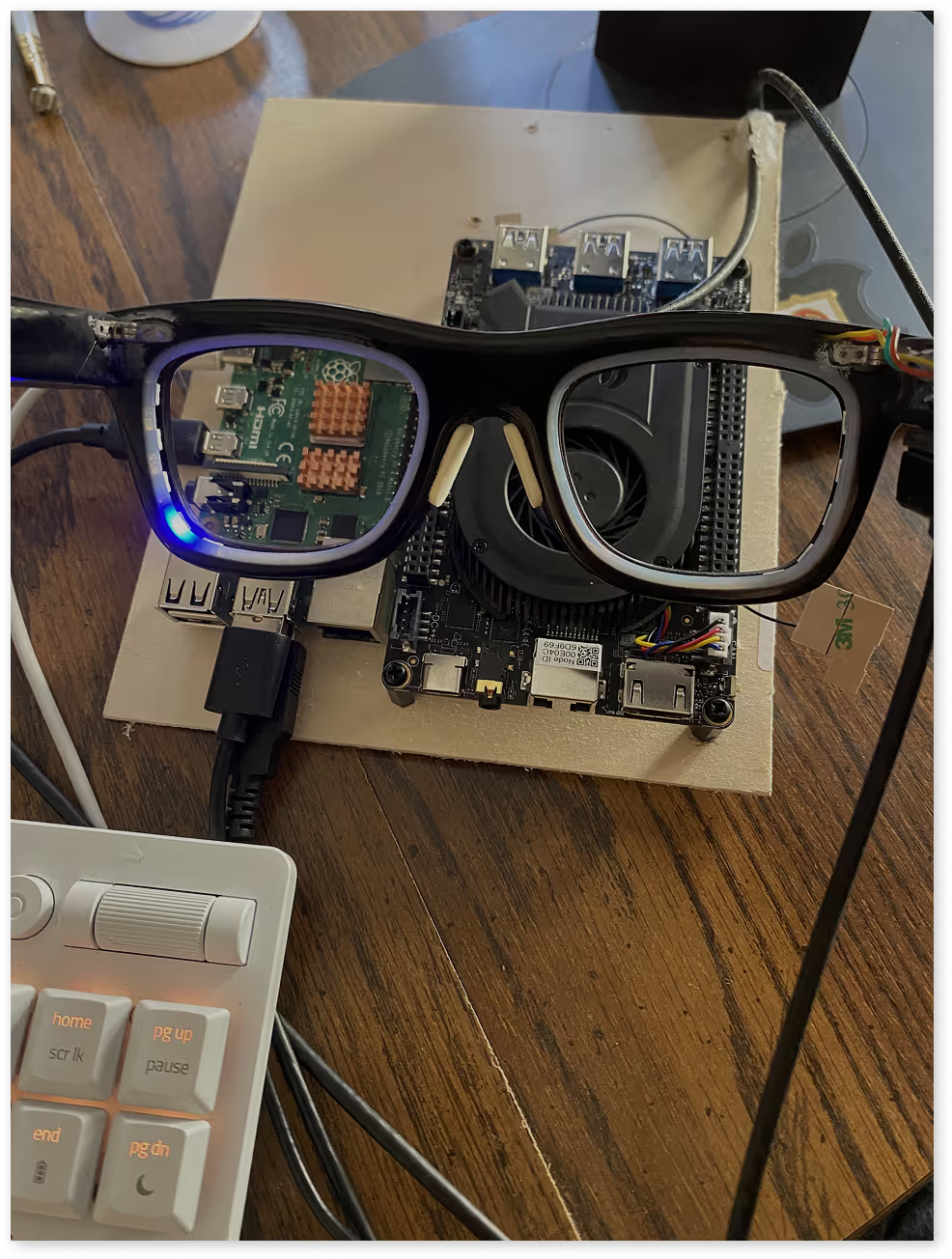

- designed and developed functional prototypes of our devices used during formative testings using Python and C++.

This was the problem ...

For those in the Deaf community, communicating with the hearing population through English is fraught with obstacles which makes having casual and unplanned conversations difficult to do.

For these encounters, they rely upon the support of interpreters to mediate between ASL and English either in-person or through video relay services. If those are unavailable, they must employ the cumbersome means of text-editors which allows spoken (or manually written) English to be exchanged visually.

Our Solution:

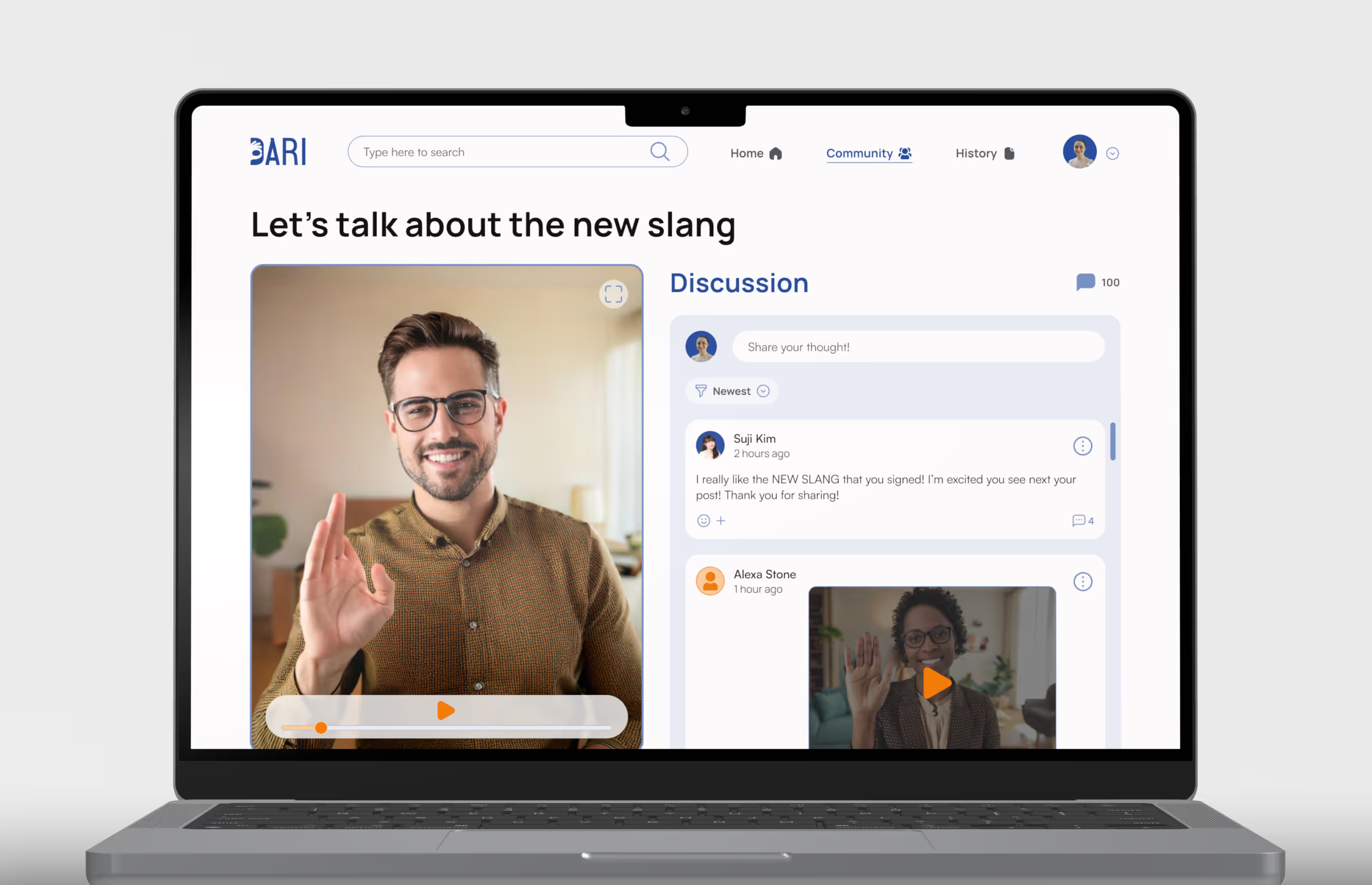

A product ecosystem employing wearables, a mobile app and desktop experience, and comprehensive AI functionality.

Together they work to interpret between ASL and spoken English by providing ASL recognition and real-time ASL captioning, as well as an awareness of the user’s surrounding auditory environment. By combining sign recognition, NLP powered interpretation, and contextual alerts, Dari enables casual encounters naturally- fostering connection and seamless interaction.

Though I could go over the full process, let me cut to the chase and tell you about what I think was the most exciting part:

How a deep qualitative approach leveraging real-time interactions with experience prototypes allowed us to define and validate a successful roadmap for our concept

Wait, you didn't start by speaking to primary users?

No, and here’s why: Before engaging with our intended users, we needed to speak with SMEs who could give specialized insight as mediators between both the Deaf and hearing communities. In other words, we were seeking a diversity of qualified perspectives pertaining to ASL, English, and their interaction. So we purposefully sampled our initial participants based on their expertise and ability to give a comprehensive view into our questions.

To collect our data, I directed my team through holding virtual semi-structured interviews which were transcribed for our dataset.

These interviews were intended to be rich and exploratory, and took queue from topic guides which probed our research questions in open-ended ways in order to elicit detailed narratives.

A Reflexive Thematic Analysis (TA)

There are many effective ways to synthesize qualitative data into meaningful insight. To analyze our transcripts, I advocated for a Reflexive Thematic approach because of its ability to foster close engagement with the data and interpret latent patterns of meaning across a dataset.

Reflexive TA: our process

We familiarized ourselves with the dataset by individually reading each transcript- looking to identify excerpts while taking notes of initial thoughts of the data. We then compared excerpts as a group and discerned common ideas we found significant. This helped us dig deep on the concepts behind the data and reflect on the developing insights as a group through the process.

After having a good hold of the data, I led our formal coding process using NVivo qualitative analysis software. As we refined our codes, we evaluated the relationships between the extracts through our own reflexive notes and with thematic maps, leading to the development of our formal themes.

Together, these four themes helped us get a vivid perspective of the relationships between ASL and English, the significance of ASL to the Deaf community, and the difficulties they face as seen through the eyes of the individuals who help them navigate the hearing world.

Four themes: four stories through the data

Because they're able to communicate with everyone around them, and so those relationships become, really becomes their family. I'm really at home, you know, I can breathe now. I'm around people who can communicate with me.

You'll see our students signing something to themselves and then on their phone typing. And then is that how I would say it in English? No. Sign it again. Tap it again. Okay. I think that's how I would say it in English. Send it. You can see them trying to put it in a language that's not their first.

The thing with all of these technologies is that they're coming from spoken English into written English right? If you're not fluent in English, and if ASL is your 1st language, it’s not going to be fully accessible, you know. You still have a communication barrier there.

Without the enrichment of the culture and worldview and value infusion and language, you are completely missing, you’re missing the person, you know, you're missing the essence of how they communicate. And you know, Deaf culture is really the representation of deaf people whose primary language is ASL.

I have to be tuned in so astutely. Interpreters are like really quick studiers of human beings because we're like, what's their tone? What's their intent? What's their goal? Where are they going? What's their purpose? Why are they having this communication, you know.

An interpretation is truly like a nuanced rendition that's coming through my ears, my brain, my worldview. And then I'm gonna put this out in a message, 3 dimensionally, in a way that is going to be meaningful, and it's an accurate representation of the person I’m representing or rendering to you.

So far, there has not been a technology that I have seen that does justice in terms of trying to address it as an automated process without having an involved human interpreter there to kind of mediate that communication. That’s, that's not kind of there yet. And there's not really any solutions.

When you just have gloves, you're removing, you're stripping the language of components of grammar. It’s distilling it down to literally hand movements, and ASL is so much more than hand movements you know.

hover over a theme to learn more ...

Behind any language is a community of individuals connected by a shared identity. For those who are Deaf, ASL is typically their first language—it’s how they build relationships and connect with others in their community. Only after gaining proficiency in ASL do they begin to acquire English as a second language.

However, the visual nature of ASL differs fundamentally from spoken language, resulting in two distinct ways of constructing and understanding meaning. As one participant noted, this creates major obstacles when Deaf individuals try to communicate effectively in English.

If interpretation isn’t available, Deaf individuals often rely on transcription technologies to convey their message. But because these tools operate solely in English, they depend heavily on the user’s English proficiency. Given the significant gap between ASL and English, these solutions pose real limitations for Deaf individuals who aren’t fully fluent; making self-interpretation difficult and miscommunication more likely.

While text-based tools can support English learning over time, they fail to reflect any aspect of ASL.This not only prevents individuals from expressing themselves in their first language, but also cuts off connection to the culture and identity that ASL embodies.

When interpretation is available, it opens communication for Deaf individuals; allowing them to express themselves and understand others in the language they’re most comfortable with. But ASL interpretation isn’t a direct translation. It’s a nuanced process involving full-body movement, directional cues, and facial expressions, as well as word choice, tone, sentiment, and environmental context.

Because of this, they constantly prioritize which meanings to convey, using their full skillset to deconstruct and transfer intent as accurately as possible. In doing so, interpreters serve as essential mediators between ASL and English, playing an irreplaceable role in bridging communication between Deaf and hearing communities.

While technology has made remarkable strides in spoken language interpretation, the landscape is quite different for sign language. Without a skilled human interpreter involved, devices often fail to capture the nuances of ASL and the fundamental differences in how ASL and English construct meaning—leading to communication that’s limited or even inaccessible.

For example, translation gloves, though innovative, haven’t been widely embraced by the Deaf community. These tools focus solely on hand movements, overlooking posture, facial expression, and directional cues—key components of ASL grammar.

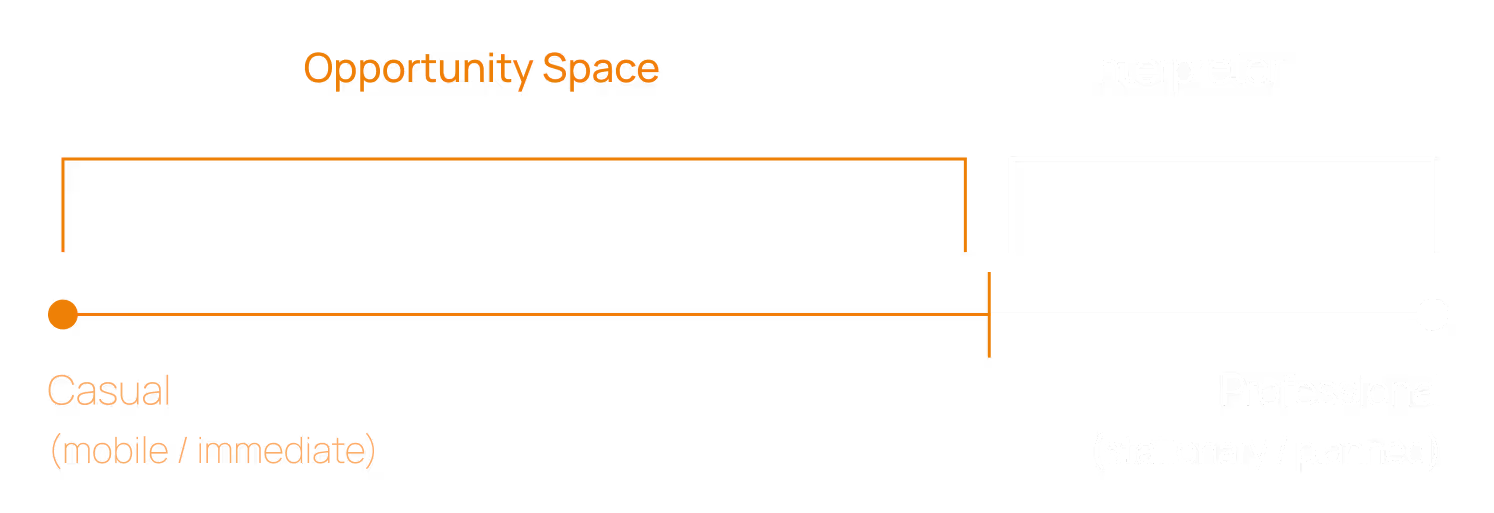

Charting opportunity and a strategy for impact

Captioning is used when interpreters aren’t available, but it poses barriers for Deaf individuals who aren’t fluent in English. Interpreters are often essential, but accessing one requires scheduling or using video relay services which still involves delays like logging in, making the call, and requesting a new interpreter if needed.

These steps can complicate even basic interactions. That’s where we found opportunity; in those moments where conversations are too quick for scheduling, but still require interpretation support.

With the scope of our solution defined, we focused our themes into 4 design criteria to guide the ideation of our solution. Click in and see…

Representing the full body in interpretation is critical in order to capture the full meaning expressed.

Provide the ability to use ASL not only their means of comprehension, but as their mode of expression.

Support a robust way to deconstruct the meaning behind the message in a way that represents the information as accurately as possible.

Provide the ability to guide how ASL is represented in order to maintain relevance and connection to the Deaf community at the heart of our solution.

Having an experience ...

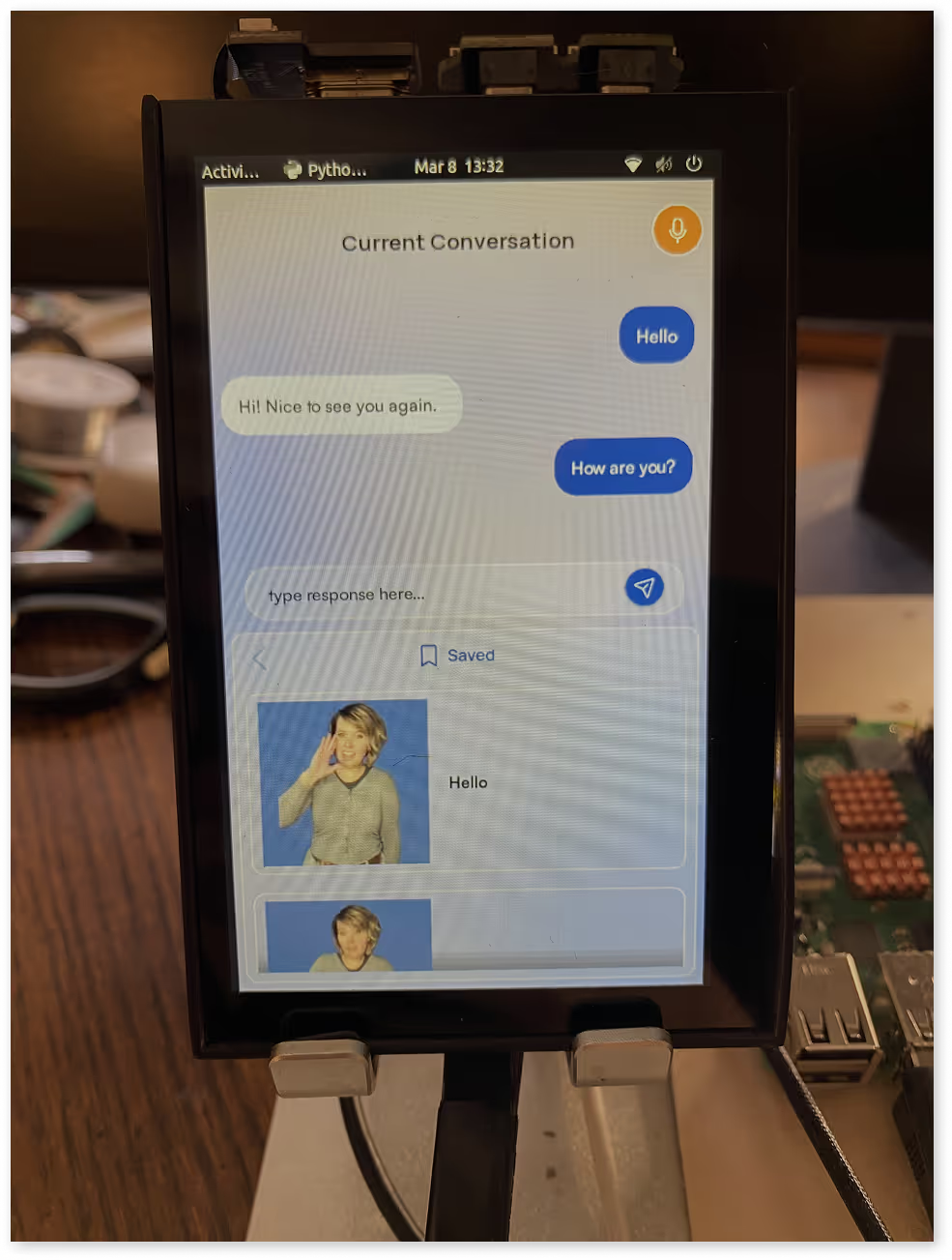

Beyond the visual design of our mobile and desktop apps, we required functional simulations to give participants a realistic sense of how our solution would work - we needed experience prototypes

To meet this need, I developed two functional prototypes: one that simulated live conversation through the mobile app, and another that provided visual cues on the glasses in response to surrounding audio.

To the field!

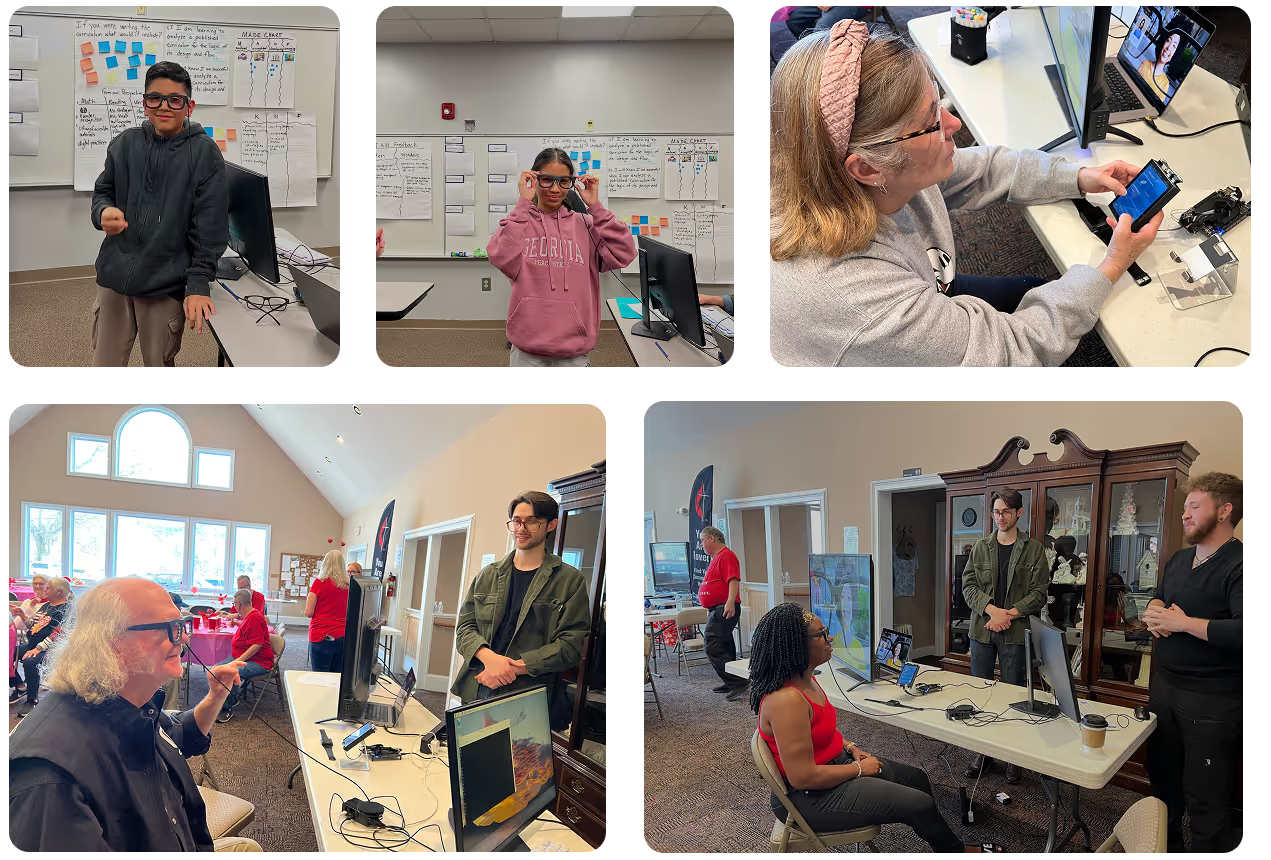

We conducted two in-depth user testing sessions—one with the Atlanta Area School for the Deaf and another with the Three River Association for the Deaf. This was our first opportunity to engage directly with our primary users, and we looked not only to validate our design direction but ground our early research

Formative testing: our process

Atlanta Area School for the Deaf

11 students

5th - 12th grade

Three Rivers Assoc. for the Deaf

15 participants

ages 27 - 70

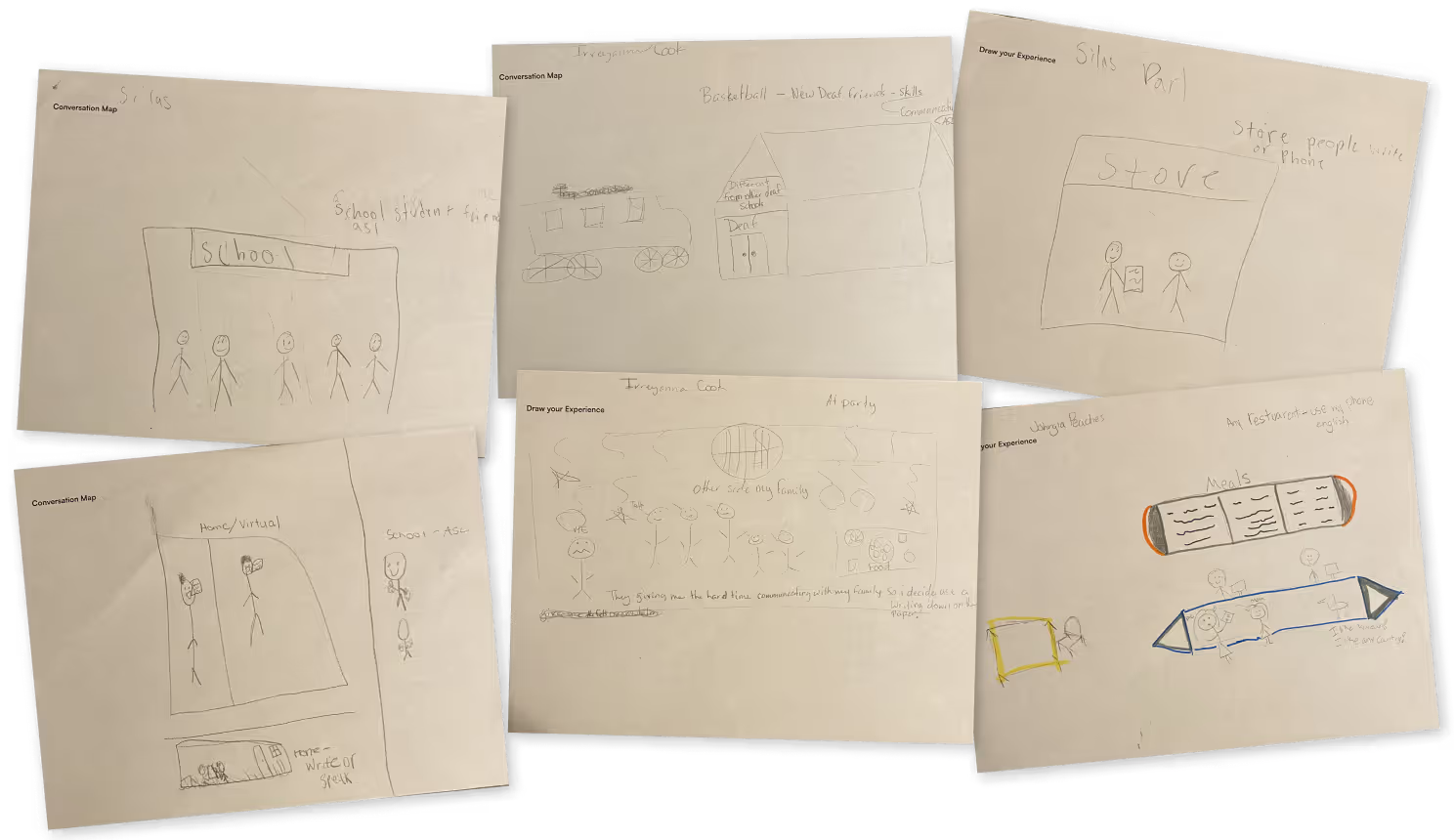

Testing began with a research activity where participants described common communication scenarios: who they typically interact with, where these interactions occur, and whether they happen in English or ASL. We then asked them to recall a past experience communicating in English, either written or through transcription, and share how it felt.

Afterward, we presented our concept and asked participants to reflect on their earlier stories and consider how our solution might have changed those experiences. To support this reflection, we provided a questionnaire. While participants filled it out, we invited them individually to test our experience prototypes in one-on-one sessions.

Validation, insight, and guidance forward

Prototypes paying off: Simulating a live conversation moved our participants from imaging how it would work to actually using it. Both testing groups emphasized the superiority of the terms in crafting their response over typing (something only a working prototype could provide), and gave detailed feedback on how to take it further. Surrounding audio queues also proved to be a very useful feature with many of our participants telling stories of when they wish they could use it.

"The sound indication is great! I’d suggest using it for baby’s crying, dog barks, and traffic when a car is honking behind me"

The first-hand accounts from participants validated our primary research. They described everyday moments where, in the absence of better tools, they rely on notebooks or phone apps to communicate simple but essential messages with hearing individuals.

Some stories were deeply personal—like a young participant who shared feeling left out of family conversations. Others described casual interactions in public spaces: ordering food, shopping, or catching a bus.